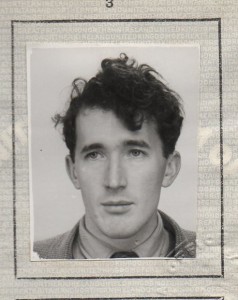

RWPMW wrote the following account of his life towards the end of 2001. Towards the end of 2008, as he approached his eighty first birthday, he had another seven years to account for. His notes on this period are appended to the 2001 text which is more or less in its original form.

The full text of Peter’s autiobiography has been broken into several chapters. The flow through the original document is as follows

RWPMW – the early working years

University to formal retirement

At that stage I think I had really lost interest in physics and would have happily taken up some other career. However I was still liable for military service which, since the war was over, was not such an attractive option and as it was possible to get a job working at Harwell as a deferred occupation I chose that. I worked on a classified (secret) project for the separation of uranium 235 from natural uranium for the civil power programme. This was the time of great hope in atomic power to solve the world’s need for a source of power to take over when fossil fuels ran out; Kennedy’s Atoms for Peace project. We also lived in the recent aftermath of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. Our project was based on the use of a centrifuge to do the separation. Our centrifuge was about six inches in diameter and span at a thousand revolutions a second. The need was for maximum rotation speed but was limited by the maximum hoop stresses in the walls of the centrifuge. In our case this was solved by a lobe structure for the cylindrical centrifuge. By heating it at the bottom and cooling it at the top a counter current was set up to induce fractionation. After three years we were never able to get any enrichment and the project was closed down at about the time I reached my twenty sixth birthday and was therefore free of any military service obligation. Since our efforts the centrifuge system has been got to work and is now the preferred means of separating heavy isotopes. I do not know why ours didn’t and theirs did work. Life at Harwell was good for me although the lack of funds was very restricting. I was paid £295 a year which even in those days was a pretty small amount. I got to know Jack Cameron in those days. We played rugby together Jack very well; he went on to play for London Scottish; and me rather badly. Our Saturday evenings were spent alternately at Scottish dancing and Old Time dancing. We had to save up to get away from Harwell which in those days was quite isolated. We lived in the Junior Staff Club which was quite a rebellious place. Jack and I stood for the house committee one year and to my surprise I got more votes that anyone else and became chairman. We used to run great parties for the residents. One Halloween with the help of our companions we had decorated the hall with witches and lots of black decorations. It was really impressive and the manageress looked in to see what was going on. She wasn’t impressed no doubt thinking that she would have the job of clearing it up in the morning. However once the party was over in the early morning those who were able to do so set to and by breakfast the room looked as if nothing unusual had happened. It was a great pleasure to meet the manageress as she came in to inspect the damage and see her face when she saw everything in its proper place. She clearly had expected to read the riot act and we had foiled her. It was also the only year that we were able to have the fees for the residence reduced as a result of my negotiations with the authorities. That gained me great credit with the other residents. But three years of that kind of life was enough. I was quite glad to get away.

From Harwell I returned to Glasgow University to study for a doctorate which had been offered to me before despite my poor showing in the exams although I couldn’t take it up then because of the military service obligation. I had saved a little money and with some help from father was able to make ends meet till I was given a junior appointment on the university staff. I started in Glasgow at the beginning of January 1954 working on a project that had been left vacant by the tragic death in a climbing accident during the Christmas holiday of the research student who had been doing it. Emlyn Rhoderick was the supervisor and the object was to measure the lifetime of some of the excited states of atomic helium by the delayed coincidence technique. This was a nuclear physics technique that had not been applied previously to atomic physics. I got along very well with Emlyn and the work went well. I inherited apparatus that was not yet working although quite a lot of the hardware was together. As a result I had a good start and had results fairly quickly. It turned out to be a very instructive experiment and I learned a lot of physics. I also regained my interest in physics and that more than any other experience set me on my career’s course. Our results were published in the Royal Society’s journal which was a major achievement for a doctorate project. Unfortunately Emlyn decided to move on to another job and I found a new supervisor in Ted Bellamy. This was a major change in physics as the object of the new project was to measure the cross-section for the photo production of pi-nought mesons at the helium nucleus. Where before I was working in the range of less than ten electron volts of energy the new project took me to three hundred million electron volts. To my annoyance the time that I had put aside to write up my thesis had to be given to this new project for which I had much less enthusiasm mainly because I didn’t have time to understand the underlying theory. However I did manage to get it working and we published a paper on it. By now, the autumn of 1956, my appointment was about to come to an end and I had to find a job. Despite my problems with having to devote time laid aside for writing my thesis to this new work I enjoyed working with Ted and we became friends so that even now (2000) we see Joan and him fairly frequently. I am sorry however that I have lost touch with Emlyn; he was a nice fellow.

Finding a job was quite an experience. It was the time when many companies were trying to get started into nuclear power. and others building up other science based projects. There was an incredible range of choices. I would write off to about half a dozen during the week and arrange for interviews at the weekend. In nearly every case a job was offered. I think they would have taken anybody. In the end I had great difficulty making a decision so I selected all the jobs that I thought I would like and multiplied the salary by the length of holiday on offer and chose the largest; this turned out to be The Atomic Energy Establishment at Harwell where I was to work on Zeta the thermonuclear machine, because they were offering six weeks holiday which was more than any other and overcame their rather smaller salary. It was a choice that I was never to regret. I started work on 1957 Jan 7 with Stuart Ramsden preparing to do spectroscopy of the Zeta plasma. The machine was still being constructed so we had to test our equipment on a smaller machine. As seems always to be the case everything takes much longer than planned so that having put it off all summer I went off on holiday for a couple of weeks in Sweden at the end of August. When I got back Zeta had started working and of all the pieces of equipment set up to study the plasma it produced mine which I had left ready to switch on was one of the few that worked! It was designed to measure the intensities of a set of selected spectral lines as functions of time during the Zeta pulse. At this time the project was secret but the decision was taken along with the Russians and Americans to declassify all fusion research. Zeta was a major part of this at it appeared at that time that it was producing thermonuclear neutrons – a sure sign that a thermonuclear reaction was taking place. It turned out that this was premature but for the time it was very exciting. The news broke on 1958 January 25 with front page headlines in all the major newspapers with our photographs all over them.

In the midst of all this Joy (whom I had met through a colleague Ken Allan) and I got engaged (1957 Oct 24) and on 1958 February 15 we were married in Oxford at St Andrews church; the best thing that ever happened to me. After our honeymoon in Malta we returned to Blewbury where, having thrown out Mike Tomlinson with whom I had been sharing Farnley Tyas, our cottage, Joy and I moved in. Mrs Quarmby (our land-lady) lived next door and was very kind to us. We had a lovely summer there before buying our own house on the other side of the village. This was an old cottage called the Forge and gave us more space. Tessa and Fiona were both born while we were living there. During the summer of 1961 I spent my evenings digging out a swimming pool in the garden. It measured 23 feet by 13 feet by 3 and a half feet deep. I used concrete blocks to line the walls, sand on the bottom and a plastic liner held in place by concrete slabs round the edge. It cost me all of fifty pounds plus a lot of manual labour.

This was also the time when I hit upon what was to be my most significant piece of physics research – which we later called ‘collisional-radiative recombination’. It started as far as I remember as a result of a chance remark by Stuart Ramsden, who doesn’t remember making it, that the intensity ratio between The Balmer alpha and Balmer beta spectral lines of hydrogen from the Zeta plasma was much greater than was found for other sources or could be explained by existing theory. I remember discussing this with Mike Seaton who thought it was probably due to the trapping of line radiation. I couldn’t see why and pursued my own ideas. I calculated, using very approximate values for the relevant cross-sections, that the intensity of Balmer Beta was reduced by the effect of stepwise excitation and that this was the explanation of the anomalous intensity ratio. This naturally lead to the extension of the same processes to all the levels of the atom and at the same time to estimates of the total ionisation and recombination rates including these processes. The forms of the cross-sections that I had adopted allowed me to calculate the rates and the spectral intensities for all hydrogen-like ions. About this time probably as a result of another visit to Harwell by Mike Seaton, Professor Sir Harry Massey heard about my work and as he was also aware of similar work that Professor Bates was doing at Belfast suggested that we collaborate. Bates wrote to me for details of what I was doing to which I responded with a graph showing recombination rate coefficients for a range of H-like ions. This convinced him that we were doing more or less the same thing and he suggested a joint paper where I should deal with the ions and he would do the hydrogen atoms. His research student at that time was Arthur Kingston. The next months were spent preparing the paper for publication although not before we each separately published our own preliminary reports to establish that we had each solved the problem independently. After many long telephone conversations the papers, for we decided on two joint papers, were published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society. This was followed by a special meeting of the Royal Society to present the work to the community. At the time I didn’t really appreciate the significance of what we had done and turned up at the meeting in an old sweater not realising that I would be on the platform in front of all those senior scientists.